|

| Williston Lake in early morning |

Built in 1968 the W.A.C. Bennett Dam is the 15th largest dam in the world by fill structure and also boasts the 8th largest reservoir. The dam itself is 660 feet high and we were able to take a tour right through the bottom of the dam and into where the penstock and turbines were located. Very impressive if not claustrophobic. We also got to drive over the top of the dam to see the spillway and generating station on one side with the reservoir on the other, all of which provided quite a perspective on the scale of the installation.

|

| W.A.C. Bennett Dam |

|

| Entrance at bottom of W.A.C. Dam |

|

| Inside the W.A.C. Dam |

|

| Gordon Shrum generating station |

|

| Peace Canyon Dam |

The Williston Reservoir is the largest body of fresh water in B.C. and measures 250 kilometres north-south by 150 kilometres east-west, an artificial lake created by damming the Peace River, it backs into the Rocky Mountain Trench and is also fed by the Finlay and Parsnip Rivers. As impressive as this source of "clean power" is for B.C. it certainly had its share of controversy following the flooding of 350,000 acres of forest, wiping out animal habitat, and dislocating the Dene people who inhabited the area. The smaller Peace Canyon Dam a little further on also has a generating station but it's the Site C dam proposal further east near Fort St. John that is really causing folks to re-think hydro-electric projects of this magnitude and this issue was something we would encounter later in our journey.

|

| Deh-Cho Travel Connector |

Leaving B.C. we now headed east through Dawson Creek and towards Grimshaw, the start of the Mackenzie Highway and route to the North West Territories via the "Deh Cho" travel connector. "Deh Cho" is the Dene name for the Mackenzie River meaning "big river". The Deh Cho route is a circular one through B.C., Alberta, and NWT connecting the Mackenzie, Liard, and Alaska Highways and it didn't take us long to appreciate the vastness of this mostly wilderness area. While there were also many tempting dinosaur museums and exhibits in this area we decided to just keep motoring along and taking in the farm country scenery of the Peace River area interspersed with all of its oil and gas projects.

The Peace River area straddles both B.C. and Alberta and, with the farming potential of the Peace River country being promoted by the federal government at the beginning of the 20th century, farming and ranching quickly took off. It is the most northerly farmland in the country and very fertile. But eventually the canola fields, elk farms, and gas fields give way to the muskeg and a landscape dominated by water, beavers and bears.

|

| Peace River crossing |

|

| Peace River crossing |

|

| Peace River |

|

| Canola field |

Originally started in 1938, but abandoned during the war years, the first section of the Mackenzie Highway to Hay River was finally completed in 1949. It took until 1967 before the road reached Yellowknife and 1971 before it reached Fort Simpson. It is on this stretch of highway that one really starts to appreciate the vastness and beauty of the North and its utter emptiness.

|

| Beaver Lodge |

|

| Beaver Lodges |

|

| Old trapper's cabin |

|

| Beaver Lodge |

|

| Sandhill cranes |

After 5 days of driving we finally hit the NWT border at the 60th parallel and what a greeting we were given by the tourism folks in their fabulous welcome centre. Photo opportunities with beautifully presented stuffed animals, brochures, travel tips, and even coffee and hot dogs. Of course Blue Boy also had to get his picture taken. In spite of all we had already seen we knew the adventure was about to begin.

The first attraction after leaving the 60th parallel were the twin Alexandra and Louise falls on the Hay River. A nice trail connected them together and you could even take a unique 138 step spiral staircase down to a footpath that got you right to the waters edge if you really wanted to get closer. A magnificent sight and the start of the Waterfalls Route.

|

| The edge before Alexandra Falls |

|

| Alexandra Falls |

|

| Hay River between Alexandra and Louise Falls |

|

| Trail between the Falls |

|

| Louise Falls |

|

| Spiral staircase to Louise Falls |

|

| Louise Falls |

We were now firmly in the middle of Canada's boreal forest, an area considered to be the largest intact forest on earth with over 3 million square kilometres still undisturbed by roads, cities, or industrial development. It also contains more lakes and rivers than any comparably sized landmass on earth and supports millions of birds, fish, and beavers. Hand in hand with all this nature is an incredible number of insects including; flies, mosquitoes, and horseflies so big they are called "bulldogs" by the locals and it was almost impossible to keep our windscreen clean as we drove down the highway.

|

| NWT horsefly -"Bulldog" |

And speaking of beavers we couldn't seem to get enough photographs of their lodges. Each one is unique and every setting is different. I really think Home & Garden should be running a contest in its next edition and award a prize for best design.

|

| Beaver Lodge |

After a night in High Level, Alberta our first stop in NWT was the town of Hay River, the "Hub of the North" located on the southern shore of Great Slave Lake where the Hay River discharges. The town is the terminus of the CN railway, the most northerly point in the intercontinental railway system, and a major staging point for the annual sealift along the MacKenzie River where barges are taken downstream to the Arctic Ocean with fuel and supplies to get most of the Northern communities through another year.

|

| Tugboats in Hay River |

|

| Hay River |

Even though it was the first day of summer and the National Aboriginal Day holiday for the folks in the north, it was a windy start to the season but I was determined to go for my swim in Great Slave Lake, the 9th largest lake in the world (291 miles long and 126 miles wide) and, at 694 feet, the deepest in North America. The water was surprisingly warm even though the ice had just finished melting a few weeks earlier and, because it was the summer solstice, it was daylight for almost 24 hours. We had reached the land of the midnight sun and what a wonderful strangeness it was.

The next day was much nicer and we headed off to explore Wood Buffalo National Park the largest national park in Canada (17,300 square miles, the size of Switzerland) and one of the largest in the world. Located at the junction of the Peace, Athabasca, and Slave Rivers (where First Nations folk have long used these intersecting canoe routes for trade) it was established in 1922 to protect the last remaining herds of bison and today there are approximately 5,000 now roaming free in the park.

With 5,000 buffalo on the loose we thought for sure we would see at least one but we drove the 340 return miles to Fort Smith and back again without a single sighting in spite of all the signage warning us they were everywhere. We did, however, see some other creatures that weren't afraid to show their faces and that included a timber wolf, a bear and a delightful marmot who was quite pleased to be noticed and have his photograph taken.

We also checked out the magnificent salt plains, a 370 square kilometre remnant from an ancient inland sea that dried up 270 million years ago, and the northern most nesting site of the white pelicans hiding out by the "Rapids of the Drowned" on Slave River in Fort Smith.

|

| Salt plains of Wood Buffalo National Park |

|

| Rapids of the Drowned - Fort Smith |

|

| White pelicans at Rapids of the Drowned |

After sampling the delights of Hay River it was time to head for Yellowknife with our first stop being another splendid waterfall, Lady Evelyn Falls on the Kakisa River.

|

| Lady Evelyn Falls |

At Fort Providence we crossed the Mackenzie River, (Deh-Cho, big river or Kuukpak, great river) the largest and longest river system in Canada and second only to the Mississippi River system in North America with the mainstream running 1,738 kilometres from Great Slave Lake to the Arctic Ocean. In June, 1789 (the year of the French Revolution) Alexander Mackenzie set off on his first epic canoe journey with some voyageurs from Fort Chipewyan on Lake Athabasca down the Slave River to Great Slave Lake and then along the lake to where it became the Mackenzie River which they followed until they reached the Arctic Ocean. Realizing it wasn't the hoped for gateway to the Pacific they returned to Fort Chipewyan in September having travelled a distance of more than 4,800 kilometres in 3 months.

|

| Mackenzie River bridge |

Until 2012 the only way to cross the Mackenzie was by boat but, in 2012 the long awaited Deh-Cho (Mackenzie River) Bridge was finally opened and the capital of NWT could be connected with the rest of the country by a year round bridge at Fort Providence. It took over 10 years to build and was millions over budget but, in the end, it replaced an inconvenient ferry service and winter ice road combination with a reliable, more cost effective solution.

|

| Deh-Cho (Mackenzie River) |

|

| Deh-Cho at Fort Providence |

Not much happening in Fort Providence except a place to fuel up and maybe get something to eat enroute to Yellowknife but it was the start of the Mackenzie Bison Sanctuary and not long after seeing our first warning sign we encountered a lonely bull strolling along the roadside. He wasn't much for conversation, especially with all the insects bothering him but he was gracious enough to pose for a photograph. In 1963 the Mackenzie Bison Sanctuary was started with a small herd of 200 newly discovered pure wood bison (as opposed to the intermingled plains and wood bison living in the Wood Buffalo National Park that struggle with diseases they've picked up from cattle) and they have since grown to a population of over 2,000 healthy beasts who have little or no regard for traffic.

Crossing over the bridge of the North Arm of Great Slave Lake we were immediately struck by all the pink granite formations popping up everywhere, evidence of the ancient volcanic action and geological disruption that formed this part of the Canadian Shield. Within this rock valuable minerals such as nickel, gold, silver and copper are found and, in the NWT, diamonds as well.

After 7 days on the road, and 3.5 thousand kilometres of forest, we arrived in Yellowknife, our ultimate destination. Located on the northern shore of Great Slave Lake just above the 62nd parallel and roughly 250 miles south of the Arctic Circle, Yellowknife was named after the local Dene tribe who traded copper tools and were referred to as "Yellowknife Indians". Once again it was a gold discovery and subsequent rush that caused it to be founded and in 1967 it was made the capital of the NWT. With a population of 20,000 there are only 20 other cities scattered across the entire northern hemisphere that are larger than Yellowknife.

First stop of course was the NWT Brewery for a much needed beverage and an opportunity to pose with a sculpture of a "bulldog". Only in the NWT where the "bulldogs" are so legendary would anyone want to honour them with a sculpture.

And there were plenty of other unique memorials in Yellowknife like the Wardair Bristol Air Freighter which was the first wheeled plane to touch down at the North Pole in 1967 and was donated to commemorate the services provided by the air freighters to transport supplies & people in the NWT.

|

| Wardair Bristol Air Freighter Monument |

|

| Bushpilots Monument |

Or the Bushpilots Monument dedicated to the pilots and engineers who lost their lives in the 1920's & 30's while flying supplies and people and mapping the rivers, lakes, and mountains. The history of arctic aviation to open up the north to mining, settlements, and military bases with all the attendant, rivalries, heroes, and technological advancements makes for fascinating reading and discovery. Yellowknife of course was at the epicentre of all that drama but, for those who take airplane travel for granted, the Bushpilots Monument also offers a great view of the city, particularly Old Town with its colourful houseboats and whimsical buildings.

|

| View of Great Slave Lake from Bushpilots Monument |

|

| Stairway to the Bushpilot Monument |

|

| Old Town Yellowknife |

|

| Old Town Yellowknife |

|

| Old Town Yellowknife |

|

| Houseboats in Yellowknife |

|

| View of downtown Yellowknife from Bushpilots Monument |

Surrounded by all that crystal clear water I couldn't resist going for my morning swim everyday. It was cool and, even though I was right in the heart of the city, I was perfectly safe in "Back Bbay" as long as I stayed away from the float planes. Float planes of course still being an indispensable part of living up north.

|

| Back Bay Yellowknife |

|

| Swimming in Back Bay Yellowknife |

|

| View of Back Bay |

Old Town is a bit like Sausalito, meets Granville Island, full of art galleries, shops and funky restaurants all along the waterfront where you can eat and drink outside and enjoy the endless daylight. Sunset in Yellowknife at that time was around midnight though it never really got dark and sunrise was around 3 a.m.

|

| Midnight Sun Gallery |

|

| Bullocks Bistro |

|

| Wildcat Cafe |

|

| NWT Brewery/The Woodyard |

|

| Stone canvas artwork in Old Town Yellowknife |

Lots of interesting outdoor public art as well, including one installation that took advantage of a natural stone canvas, various wall murals, and a collection of colourfully painted garbage dumpsters.

|

| Colourful dumpster |

|

| Colourful dumpster |

|

| Colourful dumpster |

|

| Colourful dumpster |

|

| Colourful dumpster |

|

| Colourful dumpster |

And if the painted houseboats aren't enough then a little stroll through the neighbourhood to check out the eclectic architecture, both old and new, will give you pause as you study some of the details.

|

| Funky House in Old Town |

|

| Funky house in Old Town |

|

| Legislative Assembly |

One of the main tourist attractions in Yellowknife is the Legislative Assembly. Situated on the edge of Frame Lake it is a beautiful example of post modern architecture that makes extensive use of natural light, local materials such as zinc, and themes from the local native population. The chamber itself is a circular design representing cultural traditions of the north and to support consensus style government. Stunning examples of aboriginal artwork, and a polar bear rug are just some of the thoughtful touches that adorn the facility including a translucent glass frieze that goes around the chamber to diffuse the natural light.

|

| Inside the Legislative Assembly |

Going around Frame Lake itself, a delightful 7 km trail that is a classic example of the northern ecosystem where lakes and pre-Cambrian rocks meet, as well as locals walking their dogs, there are all sorts of small birds, waterfowl and animals living amongst the grasses, wild flowers and black spruce.

|

| Frame Lake |

At only 2 km, Niven Lake trail is another nice excuse to go for a walk and along the way there are all sorts of birds, foxes and beavers to watch out for.

|

| Niven Lake |

Next to the Legislative Assembly is the Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre, a beautifully presented museum and archives for the culture and history of the NWT.

|

| Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre |

After gold was discovered in the 1930's the population of Yellowknife quickly grew and by the 1940's there were more than 5 gold mines in production. The town continued to expand especially once it became the capital in 1967 but by the 90's the gold mines were shutting down and things were not looking good for Yellowknife until diamonds were discovered less than 300 km away. This led to a new building boom and mining rush with the Ekati mine opening in 1998 and then the Diavik diamond mine opening in 2003. By 2004 they were producing over $2 billion in diamonds, vaulting Canada into 3rd place in the world by production value with other mines also starting to open.

|

| Ekati Diamond Mine |

Mining in the north is a harsh business with overwhelming logistics to deal with. Servicing the mines is done mostly by air with crews and supplies being flown in and out on a regular basis. In winter however, an ice road across the frozen land and lakes allows for trucks to haul fuel and other necessary supplies. At over 600 km in length it is the longest heavy haul ice road in the world.

|

| Trucks on the Tibbitt to Contwoyto ice road |

While mines create jobs and other economic benefits they also can create a massive environmental liability. In the case of Giant Mine (on the outskirts of Yellowknife and one of the richest gold mines in Canadian history, having produced 220,000 kg of gold from 1948 - 2004) the extraction method they used has left over 200,000 tons of arsenic trioxide dust buried underground. There is enough of this highly toxic substance to kill every person on the planet twice over and the only method officials have come up with to stop it from surfacing or mixing with the groundwater is to permanently freeze it in place at a cost to taxpayers of $900 million.

|

| Giant Mine |

|

| Contamination warning at Giant Mine |

The other major source of revenue for Yellowknife is tourism, with folks coming from all over to experience the north and see the Northern Lights in winter time, something we will be doing soon ourselves. In the meantime we will settle for another pose with a polar bear, the symbol of the North.

It was time now to say goodbye to Yellowknife and our lovely hotel and continue along the Deh-Cho route to Fort Providence. As we passed through the Mackenzie Bison Sanctuary we hit the jackpot when a herd of 60+ buffalo decided to cross our path. Couldn't say we weren't warned, as the signs were all there, and we were very happy to just enjoy the moment and take some group photos. The mothers and their calves stayed close together with the males keeping their distance and bringing up the rear. A very impressive sight.

Fort Providence on the other hand didn't have much to offer except some very spartan accommodations, great views of the Mackenzie River and bridge, and a glimpse into some of the challenges facing the First Nations communities in the North. Land claim issues are still waiting to be settled in spite of 30 years of negotiations, communities are too dependent on government assistance, and opportunities are scarce for entrepreneurship even though there is a need to provide more economical services for food, housing and power to name just a few.

|

| Mackenzie Bridge by day |

|

| Mackenzie Bridge at midnight |

The Mackenzie Highway, which started back in Grimshaw, Alberta, ends at Wrigley, a tiny community 220 kilometres north of Fort Simpson. There is a winter ice road that continues on to Fort Good Hope but plans to open it year round and connect it to the Dempster Highway in the Yukon are still in the planning stages. This would also be the likely route of the long stalled Mackenzie Valley pipeline project that would bring natural gas from the Beaufort Sea to Fort Simpson and then into Alberta.

From Fort Providence the road led to Fort Simpson, the only village in the Dehcho region and originally a fur trading site established in 1803. Originally named Fort of the Forks because of its location at the confluence of the Mackenzie and Liard Rivers, it is also the gateway to the Nahanni National Park Reserve. Leaving Fort Providence meant once again leaving the paved roadway but the conditions were good and on the way we checked out Sambaa Deh & Coral Falls on the Trout River.

|

| Coral Falls |

|

| Trout River |

|

| Sambaa Deh Falls |

Up north the distances between towns is very long and the traffic isn't very heavy. If a traveller was to break down, particularly in the winter time, you would really have to be resourceful to survive. One option might be to take shelter in an old trappers cabin, of which there are many along the way though none of them seem to have Internet service.

|

| Old trapper's cabin |

While most of the Mackenzie Highway is a proper roadway there is a section where it crosses the Liard River that requires a ferry service. It's a fast moving river and it takes a skillful captain to navigate the current and dock the boat safely.

|

| Liard River ferry |

Fort Simpson certainly had more to offer than Fort Providence in terms of accommodations and we settled into our bed & breakfast at the junction of the Mackenzie & Liard Rivers to put our feet up and enjoy the view.

|

| Confluence of Mackenzie & Liard Rivers by day |

|

| Confluence of Mackenzie & Liard Rivers at midnight |

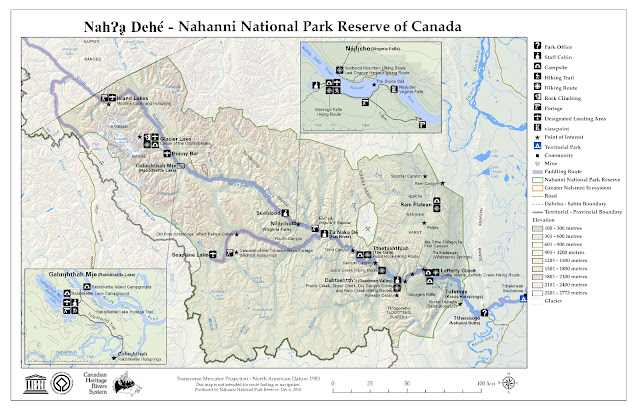

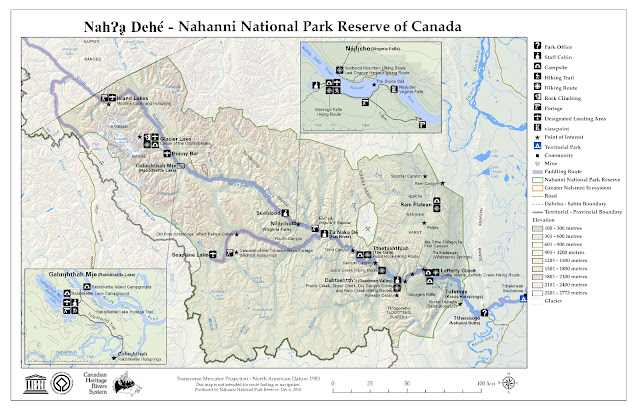

Next morning we were up bright and early to catch our charter float plane ride into the Nahanni National Park Reserve. The park was originally established by Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau in 1972 (after visiting the area and taking a guided expedition on the South Nahanni River) and covered 1,840 square miles but has since been expanded over the years, in conjunction with Decho First Nations land claims, to now cover 11,600 square miles. It has been named one of the Seven Wonders of Canada and includes the highest mountains and largest ice fields in the NWT.

|

| Simpson Air float plane base |

The centrepiece of the park is the South Nahanni River which means "river of the land of the Naha Dehe people". It flows 560 kilometres from its source 5,200 feet up in the Mackenzie Mountains, through four different gorges (some of which are deeper than the Grand Canyon) to 590 feet where it empties into the Liard River at Nahanni Butte. The South Nahanni has become one of the prime wilderness rivers in Canada and a whitewater destination by adventure seekers around the world.

Flying over the boreal forest, with its countless lakes and scarred empty patches left from previous forest fires, we quickly climbed into the mountains of the Nahanni Range and soared over the surrounding canyons admiring the unique formations created by shifting tectonic plates and volcanoes of eons past, and the various tributaries flowing into the Nahanni River. The Park is home to over 500 grizzly bears, two herds of woodland caribou and various species of alpine sheep and goats, not to mention moose, all of which can be seen racing over the ground below if you look closely.

With the close proximity of the Nahanni to the gold fields of the Yukon many prospectors also came here looking for gold. Though nothing of any significance was ever discovered there are many legends of lost mines, mystery and murder that have resulted in names like Deadmen Valley, Headless Creek, and Funeral Range for the area.

After the first three unique canyons we came to the fourth and most spectacular one, Virginia Falls. where, from Sluice Box Rapids, the Nahanni River, plunges 300 feet; twice the height of Niagara Falls. In the centre of the falls is a dramatic stone spire called Mason's Rock. From the air you can clearly see the 2 kilometre boardwalk portage trail that takes you around the falls.

|

| Virginia Falls |

|

| Virginia Falls and the portage trail on the left |

Less than 1,000 people visit the Nahanni every year, and one of the reasons of course is access. The only way in is by floatplane or helicopter and there are only 7 places where it is permitted to land; with only two of those spots available for day use visitation. One of the spots is Virginia Falls where we got out to stretch our legs and get a closer, guided tour of the falls themselves. First stop of course being the bear proof washrooms.

Meandering along the boardwalk we soon came to the Sluice Box Rapids which start off gently enough but quickly turn into a torrent of madly rushing water.

|

| Sluice Box Rapids |

|

| Ted Simpson providing perspective on the Sluice Box Rapids |

The rapids then quickly come to the edge of the falls themselves where they surround Mason's Rock before crashing down at the rate of 1,000 cubic metres per second.

|

| Mason's Rock |

|

| On the edge of Virginia Falls overlooking the drop |

|

| The drop from Virginia Falls |

|

| Parks Canada Red Chairs at Virginia Falls NWT |

|

| Portage boardwalk |

|

| Virginia Falls |

The only other day use landing spot in the park is at Glacier Lake and so, after our lunch break, we were on our way further up the South Nahanni River after a final look at Virginia Falls. Waiting for us at Glacier Lake were another set of Parks Canada Red Chairs, conveniently placed to provide a beautiful backdrop of the lake itself.

|

| Parks Canada Red Chairs at Glacier Lake NWT |

Surrounded by the granite mountains of the Ragged Range the lake faces the gateway to the Cirque of the Unclimbables, a climbers mecca that includes the Lotus Flower Tower, one of the 50 classic climbs of North America.

|

| Glacier Lake & the Cirque of the Unclimbables |

|

| Cirque of the Unclimbables |

Not being mountain climbers ourselves, we were more than happy to acknowledge that it did indeed look unclimbable and get back into the plane for the next stage of our journey which was over the Ram Plateau and into Little Doctor Lake just outside the Park itself.

|

| Little Doc Lake |

After flying through the space between the two mountains to land in Little Doc Lake, a swim was just what the doctor ordered and, with nobody watching except Mother Nature, I jumped in for a refreshing skinny dip.

In the late 19th century the mountain people of the Nahanni region would travel down the South Nahanni River each spring in moose skin boats to trade in the furs they had trapped over the winter. The boats were made of 6 - 10 moose hides that were sewn together and stretched over a spruce pole frame and were big enough to hold the entire family, their dogs, and the furs. Once they arrived at the fort the boats would be dismantled and everything traded along with the furs. They would then return home on foot with only what they could carry on their pack dogs. The Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre has one of these boats on display along with a movie that was made showing the re-enactment of this remarkable enterprise.

|

| Moose Skin Boat |

The river systems of Canada were the early highways of the fur traders who took advantage of well established First Nations routes to set up trading posts at key junctures. Fort Simpson for example sits at the confluence of the Liard & Mackenzie Rivers, and from there the Mackenzie connects to Great Slave Lake and then to Fort Resolution which is on the Slave River that flows from Lake Athabasca and Fort Chipewyan. While the fur trade had been going on for over 100 years it wasn't until the 1770's that the Hudson's Bay and North West companies started to build trading posts that would open up the West.

|

| Fort Simpson on the confluence of the Mackenzie & Liard Rivers |

|

| Midnight sunset on Liard River at Fort Simpson |

After leaving Fort Simpson, and catching the return ferry ride over the Liard River, we were now on the Liard Trail/Highway section of the Deh-Cho travel route.

|

| Liard River ferry |

|

| Liard River ferry |

While the road wasn't paved it was well graded and the greens of the forest contrasted nicely with the pretty yellow flowers lining the shoulders, and wanting to be photographed.

Of course there were also plenty of beaver whose sturdy little lodges always seem to fascinate.

|

| Beaver Lodge |

The Liard River itself was also pleasant to view and photograph.

|

| Liard River |

|

| Liard River |

While there wasn't much traffic in this neck of the woods we did manage to come across our breakfast companions from earlier who were now out fighting fires in the region.

The forests go on forever and just when you think you will never see another soul out pops a buffalo to say hello.

Originally planning to spend the night in Fort Liard, until we discovered it was a dry town, we decided to press on to more favourable accommodations and said goodbye to NWT as we crossed back over the B.C. border and headed to Fort Nelson.

Established by the North West Company as a fur trading post in 1805, Fort Nelson was the original Mile 0 of the Alaska Highway when construction started in 1942 (it has since been changed to Dawson Creek). Natural gas, forestry, and seasonal tourism are the main industries today and the principal tourist attraction is the Fort Nelson Heritage Museum. Here visitors are free to roam amongst the collection of antique cars, trucks, and equipment scattered throughout the property on the outside, tour various historic buildings and cabins, and browse through the inside of the main building with its hundreds of artifacts and stuffed animal display.

Feeling like modern day fur traders the next day had us enroute to Fort St. John, yet another trading post originally established in 1794 and given its name in 1821 following the merger of the Hudson's Bay Company and North West Company. Going along this stretch of the Alaska Highway it was once again a road that seemed to go on forever with bright green forests on all sides and off in the distance the Rocky Mountains. Incredibly beautiful and the playground of the moose, elk, buffalo and so many other creatures.

|

| Alaska Highway |

|

| Alaska Highway |

There was only one stop along the way for any refreshment but fortunately the Buffalo Inn Pub at Pink Mountain was right at the halfway point and we took advantage to make a pit stop.

|

| Buffalo Inn at Pink Mountain |

Fort St. John is the oldest European established community in B.C. and is now the centre of B.C.'s oil & gas industry as well as the centre of the surrounding Peace River farming community. Returning now to the Peace River area downstream from Hudson's Hope, we could witness both the agricultural protest to the Site C dam and the beautiful countryside that would be ruined by this project of questionable economic value.

|

| Peace River Valley |

There was wildlife everywhere you turned and beautifully tended farms with crops of canola, oats, peas and barley. To try and imagine it all under water along with all the trees just seemed wrong somehow and very wasteful.

Retracing our steps now from Hudson's Hope we passed by various rivers and lakes in the shadow of the Rockies, and in spite of the road being criss-crossed by pipeline and transmission lines, flowers still managed to bloom.

|

| Old trapper's cabin |

|

| Pine River |

|

| McLeod Lake |

Stopped for some great pizza and a little Canada Day celebration back in Prince George at the Crossroads Brewery before heading on to Williams Lake where the annual stampede was in full swing.

|

| CrossRoads Brew Pub |

|

| Williams Lake Stampede |

Incredible piles of logs were also on display at the sawmills in town where, in addition to ranching, logging and sawmilling are the major industries.

|

| Williams Lake lumber yard |

|

| Williams Lake |

Passing through the quiet, scenic Cariboo with its dry, gentle hills covered in pine trees and grass, who would have known that a week later a massive forest fire would tear through the area and turn it into a raging inferno.

We now turned off on the road to Lillooet, passing by the beautiful Pavilion Lake as we followed the Fraser River through the dry and inhospitable terrain with its steep and rocky Coast Mountain gorges.

|

| Pavilion Lake |

|

| Fraser River at Lillooet |

Lillooet is considered to be one of the oldest, continuously inhabited First Nations locations in North America thanks to being at the confluence of several main salmon streams. The town got its start in the Fraser Canyon Gold Rush of 1859 and was considered to be the largest town west of Chicago and north of San Francisco (before Barkerville took the title) and was "Mile 0" of the original Cariboo Wagon Road. It also holds all the records for being the hottest place in B.C. and the first order of business as we passed through was to find a cold beer.

|

| Bridge over the Yalakom River |

Because we had one more gold rush town to explore on this trip we had to leave the paved road and take the somewhat more perilous route along the Yalakom River and the Carpenter Lake Reservoir.

|

| Yalakom River |

|

| Carpenter Lake Reservoir |

|

| Carpenter Lake Reservoir |

The 50 km long Carpenter Lake Reservoir is a result of the Terzaghi Dam built at the head of Big Canyon on Bridge River that completely blocks the river and diverts all the water through two tunnels in Mission Mountain to the powerhouses on Seton Lake. Bridge River, used to be a major tributary of the Fraser and the most important inland salmon fishing site where the two rivers met, but the fishery is now completely wiped out. Completed in 1960 the Bridge River Power Project is B.C.'s 9th largest generating station producing 480 MW as compared to the 2,870 MW produced by the W.A.C. Dam & Gordon Shrum generating station which is the largest.

|

| Tyax Lodge |

Finally we arrived at the beautiful and luxurious Tyax Lodge in Gold Bridge where we could enjoy the views and relax with a well deserved beverage. Naturally it was also a perfect place to go for a swim and the splendid accommodations provided a perfect finale to our holiday.

However, there was one final stop to make, on our gold rush journey of exploration, and that was the town of Bralorne. Gold was first discovered here in 1897 after prospectors hiked in from Lillooet, but it wasn't until the 1930's before things really took off. From 1932 - 1971 over 3 million ounces of gold were taken from the hundreds of miles of underground tunnels that were dug, making it B.C.'s biggest gold mine, and providing employment for hundreds of men during the Depression. My father, an immigrant from Bolivia (ironically a country that probably had one of the biggest silver rushes in history when the Conquistadors stumbled across the wealth of the Incas) got his first job in Canada in the early 1950's working in the gold mine at Bralorne.

|

| Bralorne mine office |

Bralorne today is a mostly abandoned town except for a few recreational users who have restored some of the houses and painted them in bright happy colours. Others are in a state of acute disrepair but, with the price of gold around $1,500.00 an ounce, things may change as there is now renewed interest in the old mine.

|

| New home of the Bralorne Museum |

Sitting on the steps of the new home of the Bralorne Museum after looking at some of the historic photos showing men working in the mine doing the mucking (which was my father's job) and checking out some of the old mining equipment on display, I couldn't help but think about the contrast of being stuck inside a dark and dirty underground mine while outside you were surrounded by all the beauty of the forests and mountains.

With only the seasonal and rather bumpy Hurley Road to get through we were on our way home at last with our faithful, bug infested "Blue Boy" leading the way. The Chinese who were a big part of the various gold rushes in B.C. often referred to the Northwest area as Gold Mountain and, after following more than 7,000 kilometres of gold rush trails to the NWT and back I still don't know how any of those prospectors and miners did it. For most of them it was certainly a bust and, as fascinating as it was to follow in their footsteps these past weeks, I was glad to finally see the Coast Mountains come into view.

|

| Carpenter Lake Reservoir |

|

Coast Mountains from the Hurley Road

|

No comments:

Post a Comment